Previously on Blue Lard…

pp. 1-47

pp. 48-110

pp. 111-61

pp. 162-87

The following discussion of Vladimir Sorokin’s novel Blue Lard (in translation by Max Lawton) is intended for those who have read or are reading the book. It contains significant spoilers; to be very clear, I strongly recommend entering Blue Lard cold.

We’d left off with the Earth-Fucker’s successfully sending an enormous frozen cherub with enormous frozen genitals backwards in time to land in the middle of the Bolshoi Theater in the Spring of 1954. The alarmed comrades in the audience are (momentarily) pacified by Joseph Stalin’s chief advisers who are in attendance, even if their Leader is not.

In our—which is to say our historical timeline as persons in this historical world, and not our timeline as in our timeline as readers of this novel—in our own timeline, both Stalin and Lavrentiy Beria, the head of his secret police, died in 1953. But the world of Blue Lard is quite different and Beria and Stalin are both quite alive.

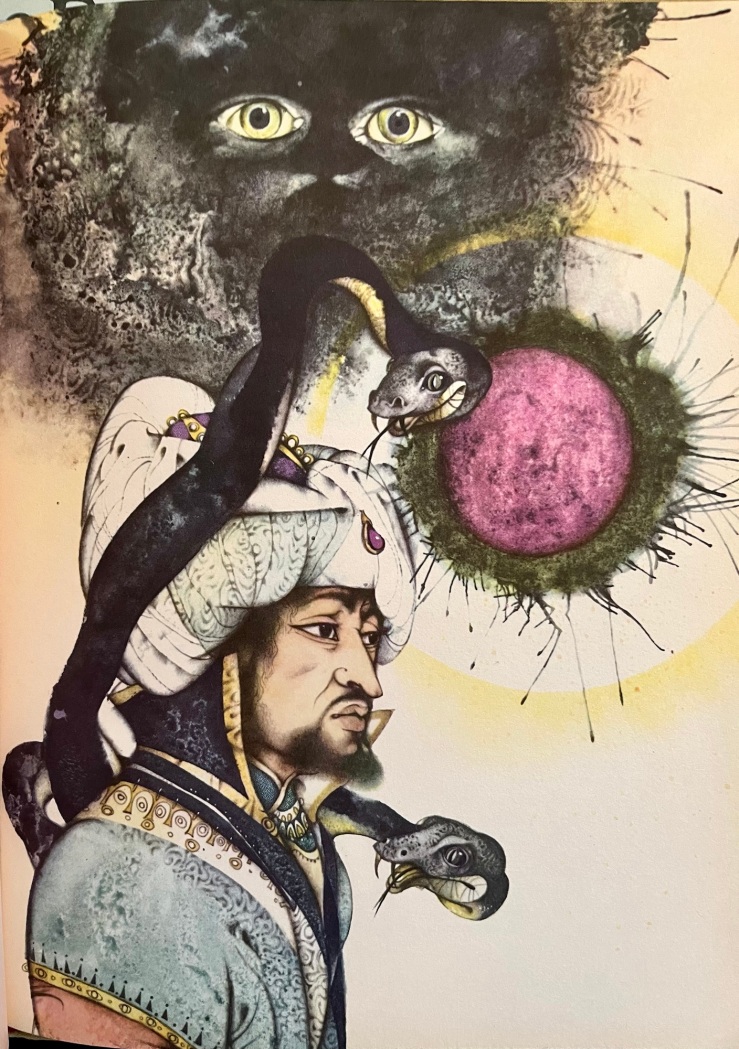

Stalin is somehow extra-alive, ultravivid, a kind of holographic pop art caricature of himself whose bearing, attire, and aura seem to owe more to glam rock and Hollywood than drab Mao tunics. We first meet him as his lieutenants try to give him the news of the time-travelling ice cone. His private rooms are opulent pink marble, adorned with Chinese rugs, vases, and priceless art, and attended by “Uzbek governesses in silk Uzbek dresses, bloomers, and tubeteikas” — all guarded by Sisul, his “personal servant” who sleeps like a guard dog upon a carpet in front of Stalin’s rooms. And Dear Leader himself?

The leader was tall and well built with an open, intelligent face that looked as if it had been carved from ivory; his short-cropped black hair was streaked with gray, his tall forehead smoothly intersected with the beginnings of his baldness, and his beautiful, black brows smoothly arched up from his lively, penetratingly brown eyes….Stalin looked to be about fifty years old. He was dressed in a kosovorotka of white silk with a silver belt and tight pants of white velvet tucked into patent leather white ankle books lacquered boots with silver embroidery.

An aging rock star. But he still has the juice.

And no wonder Stalin is aging. When we first meet him, he is berating his sons Yakov and Vasily who are in full evening cross-dress:

A long evening dress of black velvet hugged Yakov’s thin, muscular figure; it was fastened with a diamond scorpion and emblazoned with white spots upon its wearer’s miserly bosom; his curly, chestnut-colored wig drowned in the dark-blue boa around his naked shoulders; black mesh gloves, one of which was torn, reached from his thin, feminine hands to his forearms; three rings of white gold with sapphires and emeralds and two platinum bracelets with the tiniest of diamonds decorated his hands and wrists; his thin face, with his father’s distinctive features, was covered in a thick layer of powder, which couldn’t disguise the swelling of his bruised right cheekbone; his eyes, made up with blue eyeliner, were fixed on the floor; he held a thin snakeskin handbag underneath his armpit. Vasily, short and very portly, was dressed in a beige crepe-de-chine dress with a standing collar and high shoulders cascading down to the floor in tiny ruffles and embroidered with peach-colored roses upon the bosom; a large pearl dangled from his neck along a long, thin chain; his chubby hands were squeezed into white kid gloves soiled with filth from the street; though his blond wig had lost its initial shape, there was still a mother-of-pearl comb stuck into it; his chubby neck was covered with ribbons of black silk; his puffy, painted face, with an abrasion on its chin and features that very much recalled his mother’s, also looked down at the floor; a white patent leather bag on a massive golden chain dangled down from the leader’s youngest son’s shoulder.

Perhaps I have over-quoted here–and I will do so, I fear, in a moment–but I am in love with Sorokin’s lush descriptions of opulent decadence in these scenes (captured in the blue warmth of Max Lawton’s translation). Sorokin’s not exactly crafting a satire or a parody in the alternate Soviet reality he’s ushering us through. Sure, there are satirical and parodical elements and devices, but Sorokin weaves them into something odder, something harder to recognize. It’s beautifully grotesque, and while the bruised cross-dressed half brothers’ attempts to get laid in a fine restaurant and ending up in a brawl is played for slapstick laughs, there’s also real pathos to the familial dynamic Sorokin establishes among the Stalins. And, as I promised to over-share, let me give a description of the rest of Stalin’s family when his second wife and his only daughter enter (giving the half brothers some reprieve):

Both spouse and daughter were dressed in the traditional Russian style. Alliluyeva was wearing an evening dress of apricot-colored silk with a sable fringe and a pearl necklace infiltrated by a large ruby at its lowest extremity; her beautifully styled dark-chestnut hair was fitted into a samshara cap covered in pearls; hanging from her ears shone diamonds on ruby pendants and on her chubby hands gleamed a heavy bracelet and two enchanting diamond rings that once belonged to the Empress Maria Feodorovna. Stalin’s daughter’s slim figure was beautifully enveloped in a tight whitish-grayish-lilac sundress embroidered with gold, silver, and pearl; Vesta’s head was ornamented by a pearl- and diamond-covered kokoshnik and coral threads were woven into her long black braid; dangling from her ears blued earrings of turquoise and pearl and her fingers glittered with emeralds and diamonds.

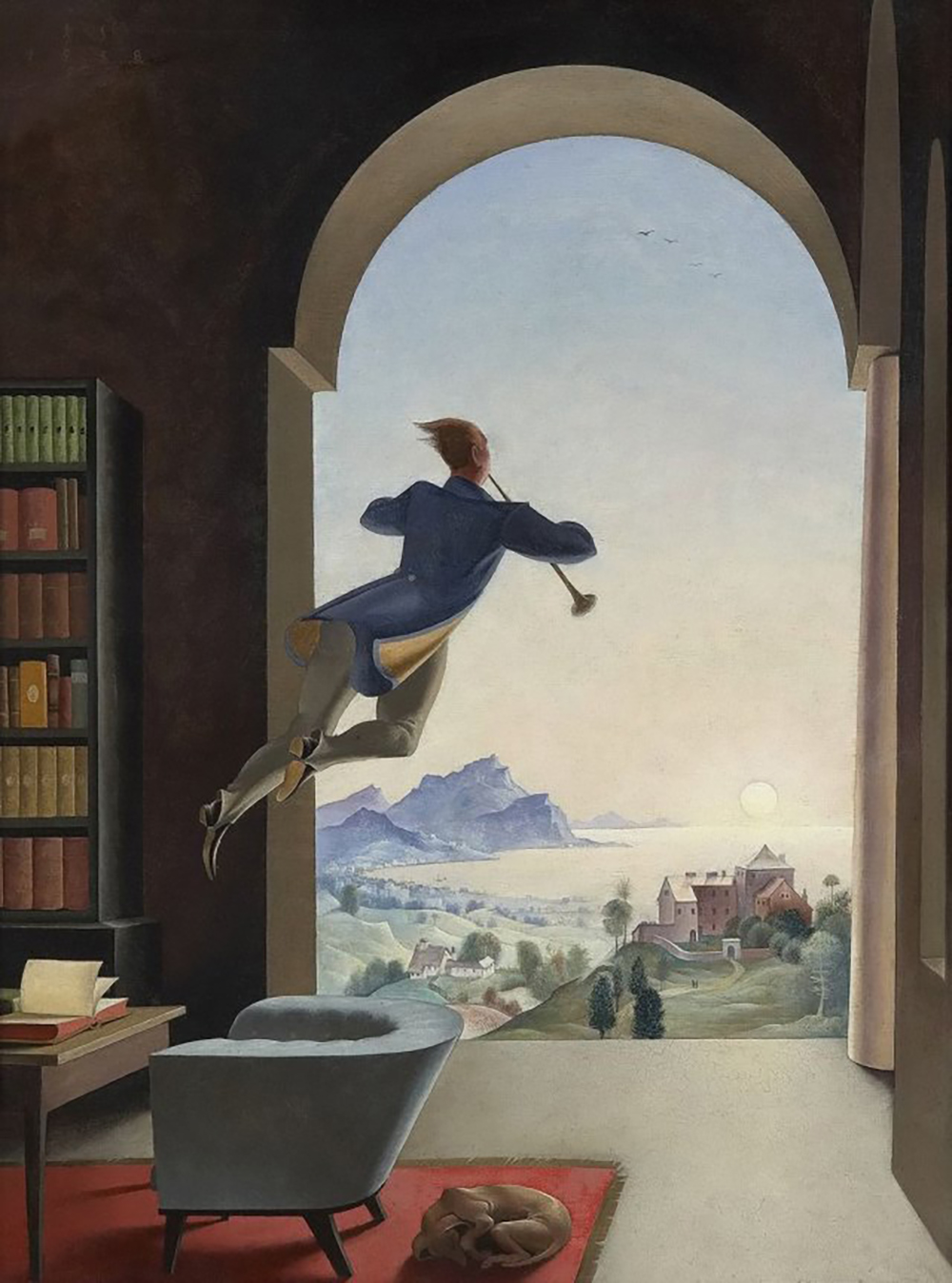

The lush decadence of the Stalin clan in the second half of Blue Lard mirrors the sordid partying of the BL-3 team way back in the future (?), in the book’s first section (perhaps the monastic Earth-Fuckers, chaste in the main, despite their moniker, mediate these depraved poles). Sorokin’s style is highly-cinematic, and the second half of Blue Lard is particularly filmic, recalling the glittery surrealism of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain. But if there’s a tinge of Jodorowsky, there’s also a big dose of Pasolini’s Salò. (Writing this now, I realize that maybe the happy (?!) medium or synthesis of this decadent filmic axis is the comedy/horror of Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover.)

Blue Lard’s Iosif Stalin exudes a glamorous depravity that’s both charismatic and menacing. Again, Sorikin crafts him into a heightened, pop art reinvention of his historical counterpart. Sorokin’s Stalin dons high-neck collars under bottle-green suits, pomades his thick black hair into a pompadour, and sports a thirty-karat emerald pendant. He’s also addicted to an unspecified substance, which he consumes in an elegant ritual involving a mobile marble column:

Atop the yellowed marble of the column, there was a thin, golden pencil case. Stalin picked it up, opened it, and took out a small golden syringe and a small ampoule. With a deft and laconic motion, he broke the ampoule, filled the syringe with the transparent liquid from the ampoule, opened his mouth, stuck the syringe under his tongue, and made an injection. He then put the syringe and the empty ampoule back into the pencil case and onto the column. This entire procedure, which had long been part of the leader’s life, described and elaborated thousands of times in dozens of world languages, captured by hundreds of film cameras, embodied in bronze and granite, painted with oil and watercolor, woven into carpets and tapestries, carved into ivory and onto the surface of a single grain of rice, glorified by poets, artists, scientists, and writers, sung in simple drinking songs by workers and peasants, was done by Stalin with such striking ease that all those present froze and lowered their eyes, as they had often done in the past.

Again, I didn’t mean to share so much of the language, but I felt myself rushing on the run of Sorokin’s long last sentence there. The decadence of Blue Lard is fun.

And Blue Lard’s fun decadence continues to ramp up as Stalin and his boys prepare for a sumptuous, sinister dinner to discuss the Earth-Fuckers’ time-travelling gift, which they bring into their dining area to observe thawing as they chow. (Meanwhile, elsewhere, Sorokin treats us (?!) to a not-quite-incestuous-but-still-disturbing-sex-scene.) Who is invited to Stalin’s special Earth-Fucker time-travelling ice-cone supper?

In addition to Molotov, Voroshilov, Beria, Mikoyan, Landau, and Sakharov, Stalin had invited Bulganin, Kaganovich, Malenkov, Prince Vasily, the sugar producer Gurinovich, the writers Tolstoy and Pavlenko, the composer Shostakovich, the painter Gerasimov, and the film director Eisenstein to dinner.

For such fine company, a fine meal must be set; again (I repeat again again), I perhaps overshare—but I’ll just lay out the appetizers here (noting that the main course Stalin’s crew will later enjoy a roast pig costumed to resemble “the Judas Trotsky”):

The table was gorgeous; Alexander I’s gold and silver tableware was laid out on a whitish-blue tablecloth, homespun in the Russian style; the abundant Russian appetizers were provocative in their variety: there was smoked eel and jellied sturgeon, venison pâté and stuffed grouse, simple sauerkraut, calf tongue and calf brain, salted mushrooms and jellied suckling pig with horseradish; a golden bear towered up in the middle of the table with a yoke over its shoulders, from which were hanging two silver buckets filled with the oily gleam of black beluga caviar and small, grayish sterlet caviar.

The dinner scene is comic and menacing, giving voices to the various Soviet luminaries and artists assembled. The filmic quality again recalls the aforementioned The Cook, The Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover, as well as the infamous dinner scene in De Palma’s The Untouchables. The violence here never reaches those limits, but it is still grotesque and climaxes in a (literal) punchline.

The night ends with the cone finally cracking, revealing “A frozen giant with monstrous genitals and a small suitcase in his lap was left sitting atop the pallet in the melted water and surrounded by chunks of ice.” Beria and Stalin share an amusing exchange about the creature’s enormous pecker (“How they must love their native soil,” Stalin muses of the Earth-Fuckers), before taking the briefcase and retiring for bed (to Beria’s apparent chagrin).

Next time on Blue Lard: The return of AAA aka Anna Akhmatova and the first appearance of Nikita Khrushchev, whose relations with Blue Lard’s version of Stalin led Russians to protest the book by throwing copies of it into a giant sculpture of a toilet—an abject pop art stunt worthy of a scene from Blue Lard itself.

Previously on Blue Lard…

Previously on Blue Lard…